The Day the Power Failed by Stuart Davis

From the now defunct Telegraph Lore site.

Available on the Wayback Machine here:

https://web.archive.org/web/20200218063219/http://www.telegraphlore.com/telegraph_tales/power_fail.html

The Day The Power Failed

{From the December, 1978 issue of The Telegrapher, published by the late

Dr.

E. Stuart Davis at his National Telegraph Office in Union, N.J. Thanks

to Bill Dunbar for providing this for use in Telegraph Lore.]

|

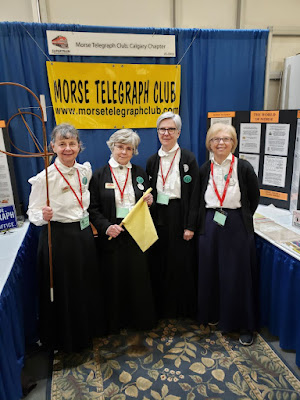

A similar office in 1945

|

It was 10 o'clock on a typical 1924 Thursday morning rush hour in the Postal

Telegraph office at 84 State Street, Boston, Mass. The model 13s of the

Morkrum mux sets to New York, Philadelphia and Chicago were pounding away,

while the iron horse xtrs were gobbling up the slips almost as fast as the

punchers could prepare them.

In the Morse department some 70 operators were moving the heavy file. The

duplexes to Ford Motor, Montreal and Portland were "doubled." At the

overflow that hit the traffic early in the morning, the clang and bang of

the Lamson slingshot (conveyor) could scarcely be detected in the overall din.

Suddenly...the lights went out! The motors on the mux ground to a halt and

the only sound in this big room was faint clicks from Morse relays on the

Test Board. People glanced at each other in utter amazement, laughed and

then relaxed while the Wire Chiefs were pounding away on the Bell wires to

New York and Albany. "We lost our power!"

Meanwhile, Yours Truly was on his way to the power room in the basement.

What a sight! A huge 1,800 ampere fuse had blown, taking with it a section

of the marble switchboard and setting the connecting wires on fire. The

basement was filled with the acrid fumes of burning insulation and it was

obvious that power could not be restored for a long time.

Back on the fourth floor, Plant and T&R; men were arranging 200-ohm local

sounders so that they could be used as main line instruments. KOB sets were

brought and plugged into table jacks and one by one, lines that could be

powered from distant terminals were coming back into service. As quickly as

a circuit was made good, an operator was hard at work moving the delayed file.

Twelve single-Morse circuits were set up to New York, two to Chicago, and

one each to Detroit and Buffalo. Anybody and everybody who could telegraph

was pressed into service - including the Superintendent and Assistant

Sup't. A hurry call was put out for the extra force - and to the retirees.

By noon, more than a hundred operators were on duty.

At several desks, typewriters had been removed and pens and ink wells

brought out. Now, the 80 year-old bonus men of a bygone era were turning

out beautiful copy at 25-30 words per minute, such as only the artists of

the turn of the century learned to do. By 1 p.m. all delays had been

eliminated and traffic was flowing smoothly.

Uppermost in the mind of the Chief Operator was the question, "What shall I

do about the night file?" On Thursdays, the average was about 7,000

messages plus an unpredictable amount of overflow press that was copied in

the main office instead of the newspapers on Washington Street. The chief

was concerned for the welfare of the elderly operators who'd responded to

the emergency call and had been on duty since midmorning. Should they be

kept on overtime, it was decided to pack several thousand "Reds" (Night

Letters) into a leather bag which was then taken to South Station and

placed in charge of an Express Messenger. New York was given the train

number and made arrangements for it to be met at Grand Central Station. A

similar course of action was followed for the traffic that moved via

Chicago - except that a DCM was given a Pullman ticket aboard the "Wolverine," due in CH at 9 a.m.

As suddenly as it had been lost, power was restored, soon after 4 p.m. A

great cheer went up! Now the mux operators who had been demoted to the only

tasks they could perform around an all-Morse office - that of "check

clerks" - were back in business, and they made those old Perforators sound

like machine guns!

With normality restored there was a gathering of top brass in the T&R;

department. Each person had their own version of the day to relate. One

Wire Chief who wrote in a very tiny hand was asked, "How many words can you

put on a blank?" He didn't know, but replied, "I can copy a ten-word

message in the space of a postage stamp." Some bragged of how many words

they could stay behind the sender, and so it went.

Finally Wire Chief spoke up: "I'm not the fastest operator around here,

but I can copy a message in French with one hand and one in English with

the other at the same time."

The Chief Operator went out in the traffic department and returned with a

message from the Montreal Duplex in French, and one in English. The Wire

Chief was provided with pencils and pads. The two messages were sent at

usual hand key speeds. He made perfect copy of both! Amid cheers and slaps

on the back, the Superintendent sent out for hamburgers and near-beer

(Prohibition, you know) and the rest of us got back to work.

As the Old Timers told us young squirts, "We handled the business about as

fast as the machines, and we were a lot more reliable."

He

practiced the profession of telegraphy in various capacities until the

key was replaced by teletype machines in 1933 on Associated Press

wires.

He

practiced the profession of telegraphy in various capacities until the

key was replaced by teletype machines in 1933 on Associated Press

wires.